An econo-graphic exploration following a money bill on its way through China

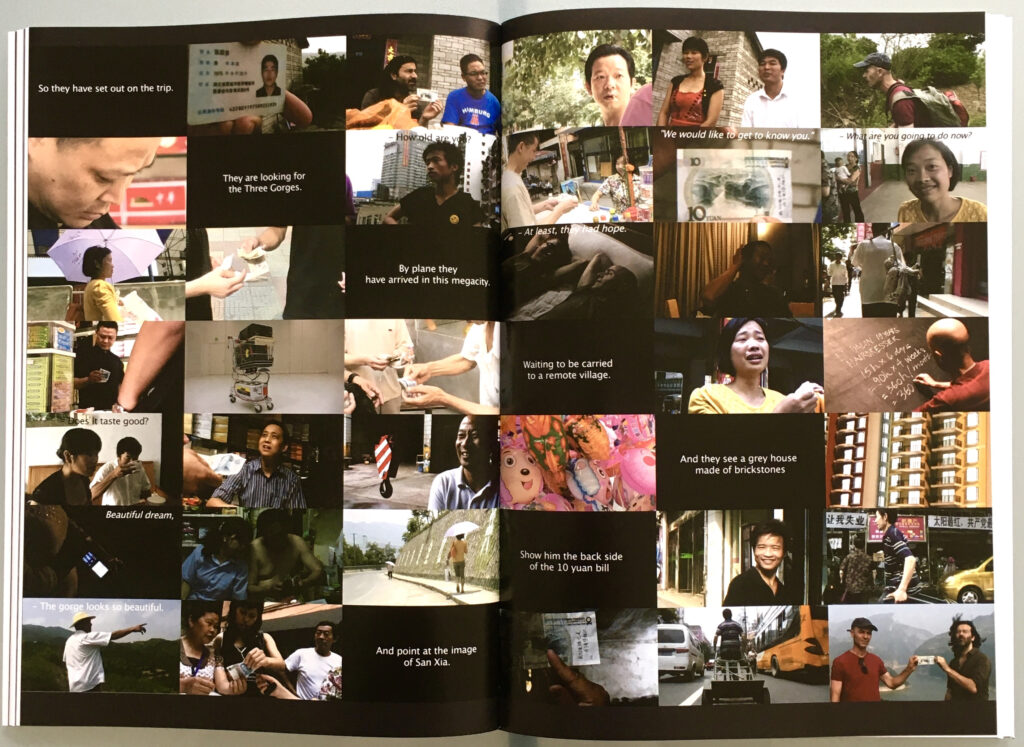

In June 2009 Peter Stamer and Daniel Aschwanden accompanied two Chinese banknotes (10 yuan and 20 yuan) on their way through China – and through these notes got acquainted with the people who were spending the money. As long as the notes were in their possession we remained with the respective owners. If they spent the banknotes, we also would change the owner. With we recorded our encounters on video and, while circulating with the money from one hand to the next, we became witnesses of everyday life in China. The accompaniment of “Renminbi” – Chinese for the “people’s money” – took us four weeks and 4,000 kilometres leading us into the individual stories and value conceptions of contemporary China. Two questions arose: Where – and even more important – who actually are the people who spend this “people’s money”?

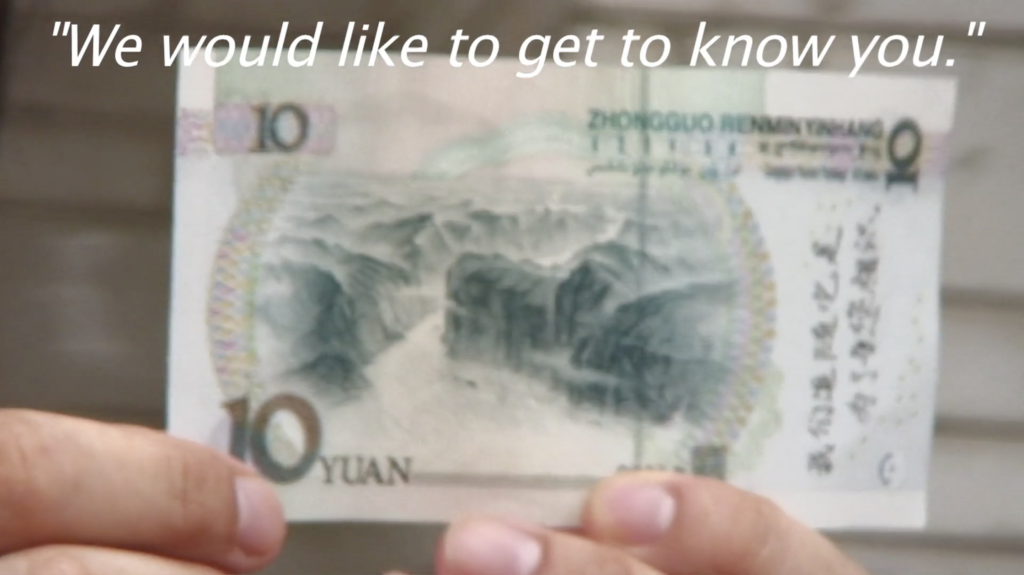

The back of the 10 yuan note shows the Kuimen, the entrance to Qutang, one of the most famous of the Three Gorges of the Yangtze Kiang. Before setting off we looked for the point from which we could take a picture of the gorge exactly as it is depicted on the note. We declared this to be the starting point for our journey into Chinese everyday life – the place from which the 10 yuan note should symbolically start its course. On 11 June 2009 we and our translator Jam Pei flew from Beijing to Chongqing in the Chinese interior. A long-distance bus took us 700 kilometres to the east. In the middle of the night we got off in a village not knowing exactly where on the Yangtze Kiang we were. We showed the back of our ten yuan note to a taxi driver who nodded and drove us to the village of Baotaping. The gorge was shrouded in the thick mist of the dawn. Somewhere above the village we decided that this had to be the point with the best view. We shouldered our rucksacks, climbed up the hill and found a white-brick house. From there we had the most perfect view of the gorge, which was slowly freeing itself from the morning mist. A man came out of the entrance, light-blue shirt, short trousers, his wife behind him. We introduced ourselves to the farming couple Chen Guorong and Cai Chunming and explained the project. They found the idea amusing and offered to sell us three pounds of peaches for the ten yuan note.

“Now we belong to you,” we said, as the tenner disappeared into Chen Guorong’s breast pocket. He was an orange farmer who also looked after the citrus grove planted all around the little hill. He had only moved with his family to this hill a few years ago because his wife had been given land from her parents there. He originally came from a small village upriver, which like so many others he had to leave as it was flooded in the course of the ambitious dam project of the Chinese Government. He had been promised 50,000 yuan (5,000 euro) as total financial compensation for his house and life, but he only received 15,000 yuan. When asked by us if he did not think that that was totally unfair he only shrugged his shoulders. Better than nothing, he said.

The following day, three meals and many hours of conversation later, we accompanied the family with their two children along small paths through the brushwood to their grandparents’ house where the pigs had to be fed. Then Chen Guorong took us to the next town, Fengjie with the intention of “selling” us and the tenner to his cousin, a restaurant owner. However, despite hours of searching in the blazing midday heat the restaurant was not to be found. Without further ado, Chen bought three packets of chewing gum from Li Qiang instead and then took leave from us and the owner of the cigarette shop. The 10 yuan note did not remain in Li Qiang’s till for long. Almost immediately after Chen had bought his chewing gum with it the note “landed” as change in the hands of a hairdresser, who bought a bottle of mineral water respectively. From there the note – and we – changed our owners in rapid transactions for cotton buds, cigars, cigarettes, mineral water and shoes until we bumped into Zhang Qiuye in front of a shopping centre.

We were just conversing with the 90-year-old shoemaker who had received the note for a pair of his raffia shoes he was selling in the street. The young woman in the yellow jumper beaming from under a purple umbrella joined in curiously and surprised us with her sudden offer. She gave the old man two five yuan notes for “our” tenner. So we came to belong to a woman in her mid twenties whom we would be accompanying for the next two-and-a-half days. She herself had come to Fengjie to find a shop to buy for her family. However, she neither knew the address and nor was she at all sure what she was looking for exactly. In Fengjie she only knew an uncle who intended to marry her off to a young man. But she was already in love with a policeman in her home city, who, however, had a wife and a child. And in the midst of explaining her situation she began to cry right in the street in front of our camera. And then a seemingly endless odyssey through Fengjie began ending up in the room of a sleazy hotel. At least for a few hours. Zhang Qiuye then decided to take the ship to Chongqing (700 km from Fengjie) with us in tow, with the ship being due to leave at 3 am. The hotel room in which the four of us were stretching out until the departure of the ship was directly by the harbor. It was air conditioned and at least for a while it protected us from the dust, noise and stench of the town. On the boat some thirty hours later she sold us to the owner of the ship’s kiosk for a dofu sausage. The note and we were thus again exchanged for some food stuff.

The next day in Chongqing: shoeshiner, money exchange, cigarettes, mineral water, two bowls of rice noodles, cigarettes, cigarettes, some newspapers, melons, mineral water, cigarettes, mineral water. Stop number 25: the water-carrier was literally in a hurry. He took the change from the cigarette-shop owner for his delivery, stuck it carelessly in his pocket and ran off. We, rucksacks on our shoulders, cameras pointing at him, ran off behind him. With a sack cart he took the road swerving through the midday traffic. At a street corner in front of his employer’s off-license shop he shouted: “LEAVE ME ALONE!” He did not want to know about us, and just as little did he want to have anything to do with the note. That was the end. We changed the banknote back and flew to Guilin, where the 20 yuan note had “originated”. But that is a different story.

Our journey with the tenner leads into Chinese everyday life, it leads to the people in the street and so into the midst of their individual and emotional microcosms. Our findings? We have met salesmen, day labourers, apprentice hairdressers, workmen, clerks, farmers, street traders, shoeshiners, the owners of kiosks, old and young people. However different their social background and their current situation are, they are all cherishing the hope for a better future. Thus the orange farmer wants to buy a clothes shop in the city in the coming months so that he and his family can move away from the village. When we ask him where he has the money from – the investment is in any case ten times his annual income of some 15,000 yuan – he confidently says that he is going to borrow the money and that he expects to be able to pay the debts back within three years. As simple as that.

Zhang Quiye, the sad young lovesick woman, is as well convinced of her economic success, regardless of which branch it may be in – architecture or garage – even if she has no idea of either. The salesman for crane vehicle accessories and party official, however, has already realized three of his future dreams: he has successfully left his home village, he calls himself the owner of an apartment in the city, of a car. For the fourth wish in his life, the one to travel to Paris once, he is only short of time, not of money. China’s new economic strength, he says, means that the Chinese can travel out around the world proudly and with their backs straight, and they can afford it. People have always been prepared to “exchange the small family for the large family”, he says thus adapting the European standard for personal relationships to Chinese conditions.

Despite the pressure of work the people are open to us, play the game with us and are just as curious about us as we are about them. Perhaps because they have been looking for a bit of a change, also because they have nothing to lose. Just like the load-carrier from Chongqing, a day labourer with a monthly income of 60 euros, which he spends on supporting his family in his home province, on a place to sleep, on his mah-jong gambling passion, and on food and cigarettes. A man at the lower end of the social ladder whose packet of cigarettes is almost thrown at his feet when he is buying it at the kiosk. He patiently allows us long-noses to question him about his private burdens and passions in exchange for a bit of attention from our cameras. As from his point of view his supposedly private affairs are nothing spectacularly intimate because the people in that little street of Chongqing share everything about their lives and work in the streets. They know each other.

Only a small section of this everyday life illuminated by the coincidence of monetary movement reveals itself to us. Our “path of money” could appropriately be described as a “social choreography in everyday life”. To a certain extent the tenner guides our movements as well as our encounters like a momentary choreographer representing the actual medium of our intercultural communication with the money interacting between us, our conceptions and the people we meet. But in the act of transfer it permits an added value, a cultural exchange within monetary exchange: Our encounters are not simply a free gift. They rather resemble donations no one has asked for without being subject to any procedural rules and with nobody reckoning with them at the same time. In this respect they are incalculable. Precisely this incalculable choreography of money opens up some space for encounters, some space for cross-cultural touching and stuttering, some space in which we appear and, sometimes stumbling, dance to the choreography of alien everyday life.

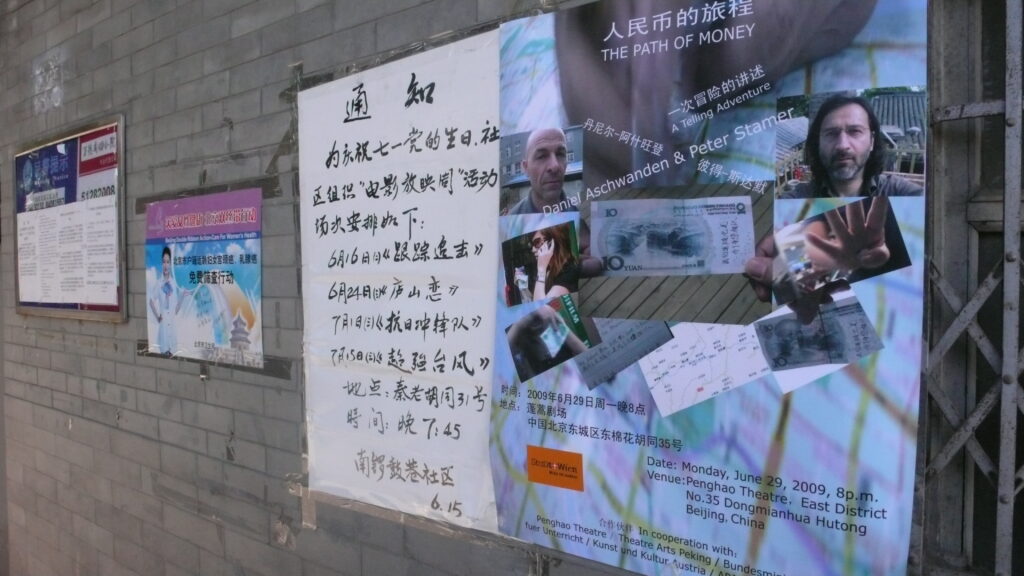

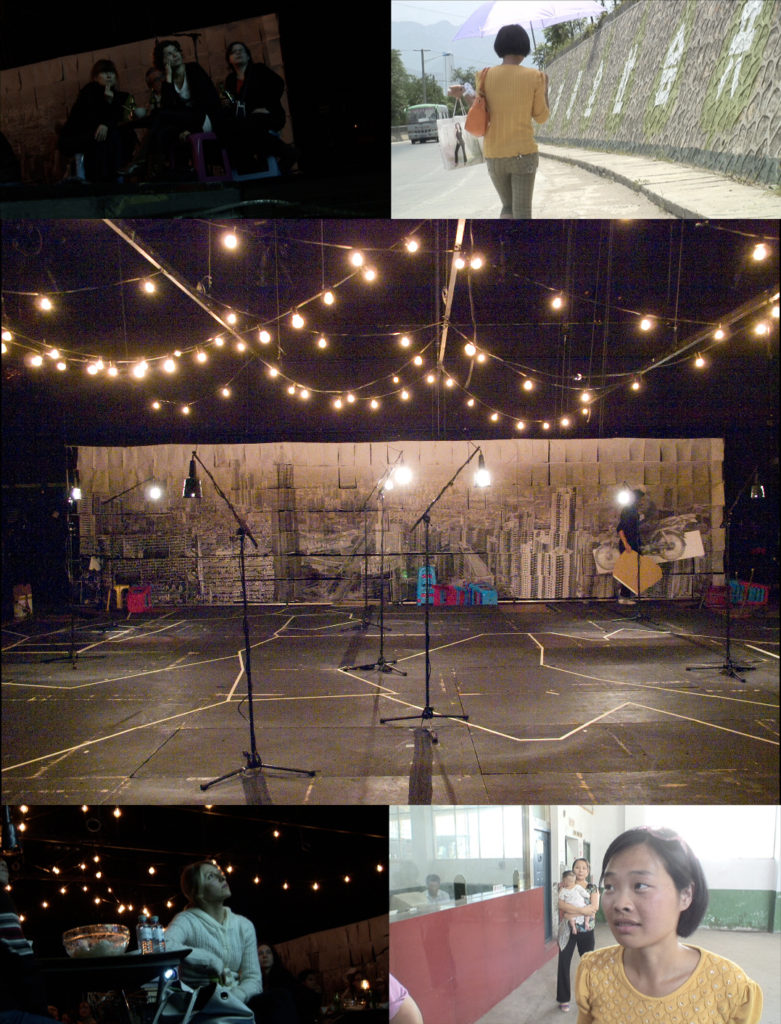

The Path Of Money_The Installation, produced and presented at Penghao Theatre Beijing, Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin, Tanzquartier Wien.

Some press reviews

“Under the challenging attribute “performance” (the performers) put the audience at Tanzquartier Wien (TQW) for 90 minutes into an unusual, impressive travelogue for all senses”.

Christine Koblitz, Kulturwoche.at, December 8, 2009

“A performative panopticon of culinary specialities and sights, far from clichés. An intercultural dialogue is created thanks to the endearing translation, which overcomes not only language barriers. A poetic walk in the service of intercultural understanding that tastes excellent.”

Laura Claire Bakmann, Wiener Zeitung, December 11, 2009 https://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/kultur/buehne/65668-Der-Weg-des-Geldes.html

“Over the last few years, a number of performances, projects and their medial and theoretical extensions have formulated a new understanding of choreography that exceeds the organization of movement in time and space: (…) Daniel Aschwanden and Peter Stamer’s piece The Path of Money, for which they followed the journey of a banknote or rather its owners during a trip to China, can be interpreted as a choregraphic involvement with individual agents of an economy that has escalated into utter confusion. (…) Cited here as examples and as representatives of others, these artists explore in their work the choreographic in other forms or media and in other disciplines, in thinking and writing – thus opening it up to the social and political. Instead of distancing dance from other discursive and artistic practices, this perspective integrates the overflowing and breaking down of barriers by the art form itself. This broadening of the term is not only significant for the practice of those artists, who have already long situated themselves between formats and forms of expression and allowed definitional dividing lines such as the differentiation of ‘dance’ and ‘performance’ to become obsolete. It also once more reveals the field of choreography as a historically grown medial hybrid, in mutual manifold exchange with the traditional genres of music, theatre, painting or sculpture and moving back and forth between everyday actions and organization, documentation and art work, live event and institutional representation.”

Sandra Noeth: Protocols of Encounter. On Dance Dramaturgy. p. 244 f. In: Gabriele Klein; Noeth, Sandra (ed.): Emerging Bodies. The Performance of Worldmaking in Dance and Choreography. 2011

Supported by Stadt Wien MA 7, Tanzquartier Wien, HKW Berlin, Presse- und Informationsdienst der Stadt Wien MA 53, ACF Beijing

And then we went to Guilin to start our journey with the 20 yuan bill …