Beitrag im Rahmen des Kolloquiums Trans-Formes am CND Paris im Februar 2005 wie auch bei PACT Zollverein Essen im November 2006

There is nothing visual beyond discourse. Not even discourse.

The set-up. Darkness on stage. One sees canvases, monitors, visual machinery, yet switched off. There is a nearly unheard murmuring on stage. If one lets one’s eyes travel, one figures out some loudspeakers on stage from where the strange telephoned voice emerges. The voice is getting louder, the volume increases, one can hear phrases, some sentences that describe a situation that cannot be seen here and now, invisible dances. Successively, visual machines are switched on, one after the other. Perhaps a slide projector, an epidiascope, for sure a video beamer. The slides go on and on, a carousel of images are thrown onto a canvas. This could be the beginning: the optical machines go to work. Three bodies mingle with them, all three of them are on stage, in silence. Texts which can be seen with the help of the epidiascope, compete with images, are overlapped with them. Videos show excerpts of the works cited by the participants. The voice of the machine is continuing its report. And perhaps once in a while, the whole machinery is stopped when the voice of a locutor is to be heard properly. It’s about visualizing how visualizing works, how text and image do intertwine, inform each other. And how the rhythm of images, their length or sudden flickering do infect perception. Perhaps the whole event of three hours is more like a radio play with images. Different voices and images interrupt a continuous academic narration. They interrupt the event like the noise of a telephone that rings and enters our everyday life as well as a comment on the said. Sometimes they function like subtitles and dub/translate the presented, sometimes they do nothing have in common, do not work as examples for the just said. Perhaps images shouldn’t at all serve as visual examples to prove the truth of discourse. They are not witnesses of something that had taken place somewhere else, instead are let alone. Also, the whole event has to take its time, it should have the chance for silence, nothingness, no discourse and sometimes a full stop. What does this rupture provide us with, how do we restart the whole machinery, in a knowledge of repetition or difference? We cannot touch dance without the help of media. The screens keep us in distance to the images. They interrupt our discourses. Although, dance is not just image, we cannot transport it into an (semi-)academic situation without the help of media which help us to exemplify dance. This procedure is in danger to take the seen, the visual for real by attributing: this is dance, whereas pure visual information about dance is just high-lighted.

Invisible Dances – “Is Any Body There?” – Seeing and Speaking

“A row of masks. Shhh. Is any body there? Masks mean they’re looking at me. Mean… She twitches. In her masks on stage stay still. Sssss. One walks away to the back. In a robe. In a red robe. R red reddy reddy they stand in a row, row, row. Broken row. Breaking inside her breaks. Another naked goes back. Backwards. Another turns and walks away to the back. Are they looking at the watcher? Is any body there?”

A woman was invited to attend a dance performance by the choreographers Frank Bock and Simon Vincenzi. She was asked to take her seat in the middle of the auditorium that was void. Nobody else sat there in front of the stage, she was the only watcher. On the seat next to her, there was a recording machine onto which spoke what she saw. She grabbed the microphone and described instantaneously what happened on stage. This show was firstly performed in March 2003 – and will be performed never again. It was just shown once to one viewer. Nobody else saw it or will ever see it again. What remains of the piece, are the textual descriptions by Fiona Appleton. One can listen to them and her voice when calling a telephone line in London where the two-hour long text is infinitely repeated by an answering machine. By this, the dance piece can just be experienced From Afar as an Invisible Dance.[1]

As Brecht pointed out, the theatre scene has already come into existence, when the witness starts to describe what he has seen. But it’s firstly a scene of words, of phrases, of gestures of search that is being established in front of the ears, not the eyes, in front of a literally conceived of auditorium. The scene of the body has shifted into the obscene (in its double sense) of a female, whispering, sometimes moaning voice. The more the vocalization tries to be precise in its descriptions, the more it is stammering, stutters, tries to find words, whispers, rocks the first consonants in order to be consonant with the seen/scene. The simultaneous production of discourse seems to fail in the face of the emergent performative quality on stage; the eye witness has transformed her perceptions into a visually incomplete medium and renders the performance obscene, off stage. By this, the beholder of that show has become a listener to a tape that is – this very moment – coming from a machine in London with which we are connected now. What was visible will never be visible, but just audible for ever. The piece is transformed into an audio piece, heard live in the very moment, as if it was described here and now, as if it took place – but rather it takes the place of a telephone that is marking direct communication. A telephone call interrupts our time, our convenience, and draws our attention to an incident that takes place far off, away from where we are, but still has an impact on what we do, see, feel. It’s the break-in of a different time, that the telephone is evoking. A rupture of time.

A piece, re-called from afar. Acoustically re-membered by an audible but invisible voice on an answering machine, keeping asking: Is any body there? There is no body seen, just its extensions which can be imagined: the voice, dialling fingers, a hand on the phone. It’s this question that answers the telephone call when no body picks up the phone. But we can’t answer ourselves and we can not talk to her. There (where?) is neither someone nor a body. Dances from afar, the medial distance of a voice that answers a call. As if there was a woman in a box like Tony Oursler’s puppet addressing us with a ‘Hallo?’. A dead, never ever lived body asking for phatic contact. A lifeless body in a technical box, facing the spectator with her voice who himself sees nothing. Can you hear my ‘Hallo?’ right now, with my voice? Those of you who wear head-phones, who do you hear, my voice or the voice of the interpreter? Isn’t it the body of an other person that greets you now? Where is my body gone?

Shhhh. Sssss. Hush-hush. A ghost in the vocal machine rendering the bodies on stage present by reporting on them and at the same time shifting them back into a never ending absence. Calling them with her words in order to ask them to appear, and mark their ever lasting disappearance with stammering words, without response. By this, the no longer invisible, but not yet visible ghosts of the performance are here, rendered present. They are not lost, but have moved on in their condition of being. They have entered the archive of presence.

The voice and the ghosts which are helped into appearance are always there. They can be contacted at any time, they can be called on in a sound archive somewhere in London, and call them into life. It’s taped, it’s categorizable, and compared to the performance it trans-forms, it’s not ephemeral. It can be heard over and over again, and therefore seems to have become a document. But a document of what? There is no monument left which it could relate to. Rather, it’s through its performance that the document becomes an artistic monument again, is monumentalized. It becomes an audible monument of in/visibility, performing visibility within the means of the sound medium. The tape makes the archive perform just by performing its archivality. So, it shifts dance performance back and forth into its invisibility by its incapability to close the gap between the seen and the described. Here, the described becomes the ob-scene, what cannot be described, what has to be left out, what is absent. It is not translatable. This rupture between eye and mouth opens up a space for obscenity: which is rendered overly present (with the help of discourse) and at the same time which is absent the eyes of the beholder for ever.

A? – Omissive body descriptions: “Can you describe the dance phrase that you have seen?” – Seeing and Writing

In her solo piece A? (2005), the French choreographer Anne Juren places herself in the middle of the stage. The audience can hardly see her right hand trembling. A spot is revealing her body. Right at the moment when she starts to move her body, the lights goes out. One can just hear her moving, but not watching her. A very short flash lights her when she is jumping, but immediately she is invisible again. After some movement’s sequences that are executed in the dark, again interrupted by flash light, she is leaving the stage, facing it from the side of the public, and looks at the back-drop where a text appears. It asks: “Can you describe the dance phrase which was presented?” Then the dancer repositions herself in the spot she started the piece from and starts again.

The audience reacts with the laughter on the sentence paradox. Although the piece took place right before the eyes of the public, it could hardly see it. Although the dancer was on stage, she was invisible, off seen. The paradox of in/visibility becomes apparently visible when the discursive instruction in its literality problematizes the very challenge of visibility. At first, the question asks the spectator a favour: Would you, please, describe what you have seen? You have seen something, but WHAT if not darkness, of winking into this black hole called theatre, if not your own blindness? What else than the visibility of invisibility could one have seen? The scene is situated in the ob-seen, the unseen, a scene of not. Flashes that blind the spectator with the help of light that should shed light onto the scene; the blindness by sight paradoxically scrutinizes the visibility of the body, makes it disappear with the help of very bright light. Although it interrupts darkness, it points back to swallowing blackness right by its brightness. It’s not visibility that is taken away here, but the to-be-seen object, subject to visibility. As visibility is the condition that renders the spectator aware that he doesn’t see, for the piece negotiates the impossibility of propositonial seeing, but not the impossibility of seeing, seeing itself. What is invisible is beyond his perception, but not perception itself.

‘Can you’ points exactly at the spectator’s competence of perception. Of course he can, but this is not just a question of invisibility. Rather, it questions the relation between senses and sensibility, between theory, stemming from theoria which means seeing, and sense making. This is the first question of dance analysis, the question “A”, alpha, Anne’s question: can you describe the dance phrase which was presented? Can you translate what you have seen in discursive language? Doesn’t the term ‘dance phrase’ itself point at the precarious relation between sayability and visibility? A ‘question mark’ is doing right this, it’s intertwining dance and discourse, but in a very striking way. Besides the metaphorical use of phrase for movement (where one can easily see that the structure of discursive language and movement don’t have too much in common) it seems that here the instruction is condensed, concentrated so that dance can come into existence just via its translation into discourse – and less in its visibility.

In the programme notes of the piece, the reader (!) can find a handful of descriptions that nevertheless were created by spectators in regards of (!)or better: dis-regards? the before projected instruction. Every single in this descriptive brochure differs from the other, they seem to fail in the face of this challenge of invisibility. It’s more or less up to the imaginative powers of the spectator what he presumes to see on stage for he can’t see a dancing body. He extends the images that he doesn’t see and adds new ones by his speculation. Specters of Anne. The impulses for analytical discourse, implemented by this projected sentence, phrase, do lead to an over-production of words and by this, render language mute: about dance and its obvious visibility, language has too much and nothing to say.

So is this discursive failure total, regarding dance in its double sense of the word? A discursive failure that seems to be the curse of analysis? Yesno. Noyes. A? shows that this discursive failure seems to be the only way to make dance visible. It seems to be that the produced ‘dance phrases’ are necessary to mark dance as the non-discursive. It’s not dance that resists translation into language, rather, dance is set into the light of discourse, in the enlightenment of language and therefore becomes visible, be it executed in the dark or also in beams of light. Not what you see is the main task of dance analysis and descriptions, but what you say and thereby render visible both the unseen scene and the seen scene.

And Juren is turning the screw once more. In a second step, she uses the descriptions of the programme notes as instructions for choreography in the course of the piece. She makes use of them as a partition, a libretto, in order to produce variations of the first, original dance phrase presentation. She hereby retranslates the written dance phrases into dancing phrases, and by bringing them on stage, she suspends them into the dark, opaque, obscene. What is written in the darkness of the auditorium, by a blinded spectator is retransferred onto the blindness of the stage. What couldn’t be seen but just written, becomes a text written in ‘stage braille’ that just can be executed by a reading, that needs the help of a dancing finger which is extended into the dancer’s body. With these gestures, she reads and conducts her physical discourse and de-scribes the discursive descriptions into the darkness of choreo-graphy. A? is an interruptive text is a rupture of visibility in the light of the visual.

[…] – the Omission of the Body: “We are alone at last.” Gestures in film and dance

The spectator is looking into a bathroom. The camera directs the spectator’s gaze right to the tub, there is water running out of the shower, but no body is washing herself. Cut. Back to the door frame, it is shown in a close up. The front of it well-focussed whereas the backside of the room is out of focus, not really sharp. Then the camera moves, it makes half a turn, showing a cosmetic board, with some cream pots on it. The whole room is empty of bodies, nobody is visible, there. But there is something strange in that whole scene. An atmosphere of tension, a close look on something that still is present, that resists absence.

In […] (read: Omission), the Austrian choreographer Willi Dorner gets down to questions of physical and medial presence and absence on stage, in film and in music. In collaboration with French composer Georges Aperghis and Austrian film maker Martin Arnold, Dorner scrutinizes the very notion of ‘ob-scene’. Under this heading, the production negotiates presence and absence of theatrical bodies, medial figures and sound appearances. Thereby, two meanings of the notion are focussed. On the one hand, the latin word ‘ob-scaenum’, originally stands for the ‘invisible’, objects that are not meant to be shown on stage, being too filthy. On the other hand, every-day language uses the word ‘obscene’ in order to mark all too explicit and overly visual practices. In this dimension of in/visibility, the interrelation of (dancing) body in theatre and (medial) figure in film shall be located: to which extent do dancing bodies visibilize phenomenons beyond their physical presence, what deprives the film-figure of the spectator’s gaze?

In order to materialize these two notions of obscene, […] shows a porn movie where the protagonists are visually erased, decomposed. With the help of computer technique, frame by frame, Arnold could take out the shapes and bodies of the film. What is visible are just empty (bed-)rooms. The procedure of ‘de-composition’ can be seen as a central concept for the transformation of these questions, a strategy that Willi Dorner, Georges Aperghis and Martin Arnold made use of for their choreographical, musical and filmic work. In the respective field of work, the procedure of de-composition deprives the work of an essential component (that would be necessary for narration, formal structure and production of meaning) in order to open a space or a ‘zero’-element that substitutes the before present component. Although this ‘zero-element’ still follows its function for representation, it suspends representational elements into the dark, opaque of invisibility. With the help of complex computer technique, Martin Arnold erases film figures from found film footage, and by doing so, he points at their absent presence that inscribes itself into narration and representation. He makes visible the paradox of presence through absence. He can do so by counting on the spectator’s knowledge of visual dramaturgy, of the mediality of film.

The spectator has to complete the scene in his head with the help of his own imaginative movements. He has to fill in the visible gaps what he knows of this genre in order to understand what is going on there: a porn ‘is shown’ out of which mating bodies are erased. The sex scenes that have been taken out of the original movie by digital effacement are displaced into the head of the spectator: brain fuck. So, what is not shown on stage is transferred into the obscene imaginative space of the spectator where the scene of invisibility is manifested at first hand. The relation of in/visibility is precarious as the visible needs a clear allusion in order to appear, but just as a marker of what is not shown. The visible is just pointing at what is not on stage and not in film, be it bodies, movements, gestures.

Visual absence here is narrative presence. Martin Arnold is not just taking the figures out. Rather, he replaces the figure with one could call a ‘Zero-figure’ that works as a stand in. This figure is not just not there, but it can be seen if you look at the filmic back-drop in front of which the figure is missing. This background is not sharp, is out of focus. Thus working like a marker of absence, it marks the former presence of the figure which was right in the focus of the camera shot. The absent figure still claims its function, so to speak, it’s figuring as a figure. This ‘Zero-Figure’ can be made out exactly because of the background’s unsharpness. So in Arnold’s work, the figure still claims its function of narration even if it’s absent.

In the context of the piece, the discourse and images of pornography is not used for the sake of showing sex, intercourse, sensational orgasms. Rather, the concept of pornography is here used amongst others as an example for filmic narration. Pornography initiates two semiotic figures, but just in order to de-figurize them into bodies, for the sake of physical sex, for their bodies, their anatomical details. But as it turns out, desire and lust can not be shown: the pornographical narration hinders lust to be shown, it’s the unrepresentable, it cannot be symbolized.

The moment the protagonists take off their clothes, the bearers of their social status, the markers of their roles which are overly displayed in porn, they lose their characteristic social traits. What remains are whole body holes, opaque, dark on which the camera tries to shed light by zooming onto them, by closing up. But whose foot is that, whose body part belongs to whom in such total close ups? The markers of male and female sex have the tendency to become invisible. By putting the bodies under the looking-glass of the close-up, the overall obscenity of sexual representation becomes ob-scene, off stage, in-visible. At the end of the metamorphosis of erotic figure to sexed body is an anamorphotic body, twisted, dissolved, an-erotic.

By this, porn itself has the tendency to erase lust and desire as it is incapable to symbolize it and to inscribe it into desire. Desire remains absent, but in its absence, the figure of pornographic discourse is permanently present. Lust or jouissance is alluded to as being absent via the frame narration and also by the execution of intercourse. It is shown to be represented by figures and presented by the body, but it fails for jouissance just can be represented as sex that hasn’t yet taken place or is no longer erotic in the presentation of bodies. By this, jouissance cannot be shown within the means of porn movie: jouissance figures as the functional zero-element of porn itself. It’s rather a black hole that sucks what is there and swallows what is visible.

By this, the three dots in brackets as one can read the title literally do not form a name. They are no stand ins in order to signify the insignificant. Rather, they form themselves an omission statement, even negating visible word, visible name: disfigured and nameless.

Omission Statements

These three performances challenge the notion and the very phenomenon of visibility. Whereas Invisible Dances do point at the precarious and instable connection of watching and speaking, A? takes on that relation and at the same time destabilizes it with a visual paradox: as one can see that he sees nothing, what is left to be described? […], in full light, doesn’t even show bodies although they are meant to be present: no body, nothing can be seen. By scrutinizing the performative potential of the ‚obscene’,[2] all three productions not only try to challenge typical ways of representation in radio play, film, and dance; they also want to bring to the fore a problematization of the audience’s scopophily that is however not satisfied as by the invisibilization of the explicitly visible, the stage is set as a kind of reflective counter-locus: a place which throws a light on the invisible gaze and reflects it back at the same time.

But what is the relation of the visible / invisible to epistemic operations? Where is the suture that links discourse, text, and visibility? That starts off in order to bring the in/visible into interplay with the sayable, ‘dicible’ (‘le diciple’ is the pupil that has to say what the teacher tells him)? Deleuze sets the relation between the visible and the sayable as knowledge. But how to gain this knowledge without getting paralyzed by what the beholder sees? How to translate between the seen and the said?

In order not to be paralyzed by the performative events on stage, one has to “draw a distinction”. Due to the logic of George Spencer Brown, this is the first and unquestionable operation of cognition in order to gain knowledge of and about what we experience or think. If not, everything would be regarded noiseful, undiscernible. It becomes apparent that even the experience of noise is not beyond an operation of distinction: to be able to recognize noise, one had to draw a distinction beforehand, that enables him to discern noise as noise. It’s this propositional operation that makes objects, things, the world outside discernible – and by this, marks them. Marking as something is the effect of an epistemic demarcation.

As a method of distinction, demarcation separates two sides, A and Not-A (or, call it: B), it draws a border-line between at least two events, perceptions, situations in order to be able to distinguish them. So, demarcation is a method to mark things as different from each other. Performance analysis makes use of this operation as performance analysis functions as a tool that translates dance into language in order to gain knowledge. If it’s true that translation of art into discourse is in the core of art theory, as the German philosopher Wolfgang Iser puts it, than the to-be-analyzed is already separated from the one who analyzes.

The practice of art necessarily becomes the other of discourse. Not to be able to overcome this procedure, as this is necessary to produce sense of what one with the help of one’s senses perceives, this but leads to a dead end. In the attempt to translate art into discourse, one undergoes the experience of failure as art is not fully translatable into discourse. It’s how Adorno put it, not only the enigma of art that eludes translation, it’s the status of art itself: if art could be fully translated into analytic discourse, it wouldn’t be art. Does it seem to be that the unhappy situation of paralysis in the face of art, having been changed into the happy situation of distinction is not so happy again: analysis again seems to be paralyzed by the performative events on stage.

Hence this relation is precarious as dance and discourse seem to be exclusive one to the other. In quite a complicated epistemic turn, performance is distinguished as the other of performance theory in order to be able to make it an object for scrutiny and at the same time, the enigma of art can be stated as an intranslatable remnant, undiscoursifiable and in the end ontologically untouchable (see Phelan).

But this phelanesque conclusion cannot be conceived of as being valid. Rather, one has to take into consideration that these differences funtion as epistemic effects of a discursive separation that enables the production of analytical knowledge and renders art and theory as their different ‘other’. As this otherness is far from being an ontological state, but rather a product of an epistemic operation, the demarcation of both art practice and art theory functions due to the work of a differential that marks both fields ‘as the other of its other’. So theoretical attempts to examine the interplay between art and theory (e.g. to find adequate methodological tools to translate dance into discourse) should concentrate on the epistemological differential that separates and combines dance and discourse at the same time and less on the products of this separation. Thereby, the act of distinguishing itself is to be looked on.

Three operations of differential logic

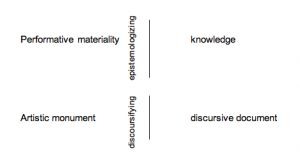

It’s obvious that the act of distinction is bound to discourse. The discursive production of difference is hereby itself an operation that follows at least three path-ways:

It renders the mute performative event speaking by epistemologizing its sayability: it imputes sense and knowledge that has to be dug out of it

It renders the dance monument visible by discoursifying its visibility: it documents its visual status with the help of texts, verbal descriptions or discourses

Thereby, it restitutes the performance by declaring its ephemeral, volatile, non-discursive status: the differential is fostered by the archive that regulates the conditions of sayability and visibility.

Dance performance can therefore, thus theoretically radicalized, be seen as the effect of distinguishing discourses that regulate the relation between what can be seen and what can be said about the seen. Therefore, dance performance’s enigma, its ‘intranslatability’ is the effect, too, of an enigmatifying procedure that is, however, necessary to steer the theoretical discourse on art. It’s the archive conceived of as by Foucault[3] that regulates and conditions the procedure of enigma.

[1] “Invisible Dances – From Afar” was divided into two acts, each consisting of 18 scenes of three minutes and 20 seconds. Every scene is framed by the opening and closing of the theatre curtain.

[2] The latin word stems from ‘obscaenum’ which can both be interpreted as filth (what should not be shown) and off the stage of visibility.

[3] According to Foucault, the archive defines the system of sayability of an énoncé which at the same time is the first element of discourse. An énoncé like a flash crosses discourse and regulate by this what a discourse can say and what it cannot say.

Dieser Text ist ein Beitrag zum Dreier-Vortrag von Franz Anton Cramer, Katrin Schoof (Visuals) und Peter Stamer, der im Rahmen des Kolloquiums Trans-Formes am CND Paris im Februar 2005 wie auch bei PACT Zollverein Essen im November 2006 gehalten wurde