A performative installation project by Peter Stamer with Jörg Laue and Alain Franco

Researched and realized at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York

Artists in Residence from Monday, March 10, 2014 – Sunday, March 23, 2014

A work-in-progress performance: Saturday, March 22, 2014

In three sessions between winter 1988 and spring 1989 philosopher Gilles Deleuze, sitting in his living room, faced up questions of a television crew. The principle was as simple as sophisticated. The topics he was confronted with followed the letters of the alphabet – one letter, one concept, from ‚A as in Animal’ to ‚Z as in Zigzag’. To avoid zig-zagging in his discourse, Deleuze received the list of topics beforehand and thus worked assiduously on the answers he then extemporized on during the recordings.

It’s the pleasure of both the arbitrary form and Deleuze’s way of thinking through his famous concepts that makes the ‚Abécédaire’ so fascinating: 26 earnest, witty, and instructive seven-and-half hours of philosophy-on-the-go. There was only one condition Deleuze insisted on. Since he didn’t think much of television the program was not to be aired before his death. Now, some 20 years after Deleuze’s suicide by defenestration in 1995, Peter Stamer, Jörg Laue and Alain Franco, coming from Berlin and Brussels, approach Deleuze’s ‚Abécédaire’. Drawing from their individual artistic practices as directors, dramaturgs, video artists and musicians they draft 26 performative letters toward the concepts both of the alphabet and the philosopher. A venture too big to undertake, and yet: „If one doesn’t feel the shame of being a man there is no reason to create art,“ says Deleuze.

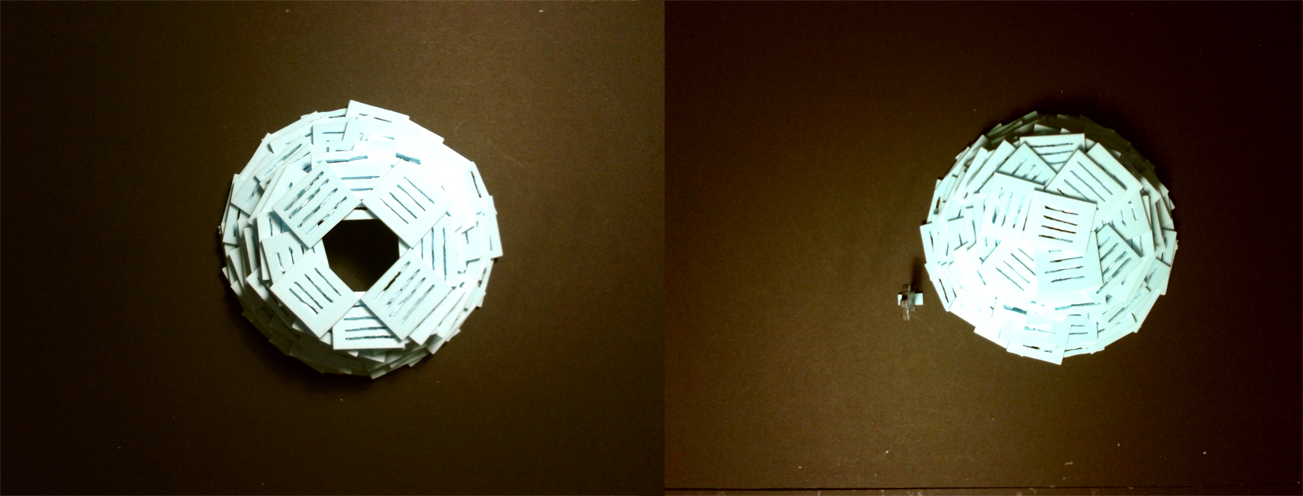

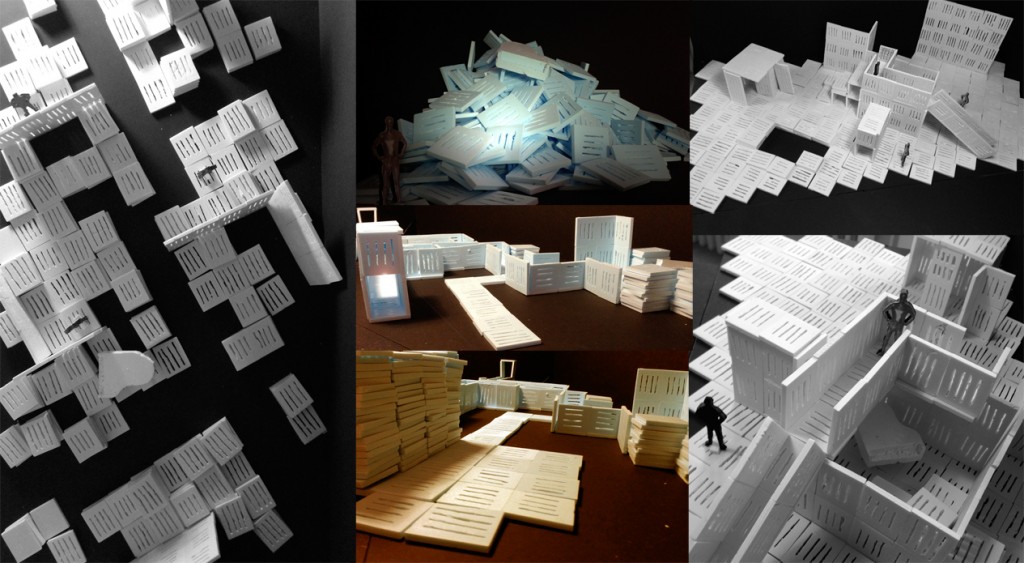

3 Artists – 26 Letters – 500 Pallets – 1000 Plateaus

A living room. An old man with glasses sits in an arm chair. When he lifts to speak he sometimes takes his binoculars off and makes them slide along his fingers, avoiding to touch his overlong fingernails. His hair is uncombed, his red pullover seems worn out. Behind his arm chair there is a chest of drawers, in mahagonny.

Deleuze’ ‚L’Abécédaire’ serves as a source of inspiration rather than a performative blue print, since the order of the alphabet Deleuze agreed upon for this interview is rather a means to display contingency and arbitrariness. Each word completing a letter could have been a different one. Claire Parnet mentions this fact before introducing the letter ‚F’. Since the letter ‚A’ has already been used for ‚Animal’, she has to use ‚Fidelité’ instead of ‚amitié’ (= friendship). To this extent, each letter works as initial in order to initialize, to bring forth a thought process rather than creating a lexicon or dictionary of Deleuze’s philosophy. The alphabet serves as a playground to at least start somewhere.

On top of it, to the right, there is a metal pole attached from which an old hat dangles, next to it a pile of files or texts. There is a bowl on the commode’s centre with a lot of matchboxes, and to the left there is a dimly lit lamp, with milky stained glass. Hanging right above the commode, in a baroque-style frame, there is a large mirror in which we see the face of a middle-aged, brunette woman.

Deleuze prepared the interview beforehand. Even without knowing the exact concept behind a given letter he was informed about the direction the talk would take, and thus could draw from his vast philosophical oeuvre (Deleuze is sometimes seen looking at notes he took down before the encounter). The letters offer cues to apply his discourses and reflections and open test fields for (not just his) aesthetic thinking; Deleuze can’t philosophize without the arts: „Whether through words, colors, sounds, or stone, art is the language of sensations. Art undoes (…) in order to substitute a monument composed of percepts, affects, and blocs of sensations that take the place of language.“ – „Percepts are no longer perceptions; they are independent of a state of those who experience them. Affects are not longer feelings or affections; they go beyond the strength of those who undergo them.“ (Deleuze: What is philosophy?)

We behold bookshelves behind her face in the mirror, packed with lots and lots of books. The woman as we learn is called Claire Parnet. She listens carefully when the older man answers her questions, sometimes with a cigarette in her hand, sometimes scribbling notes down on a notepad she balances on her knees. Both, the man and the woman, never seem to see us, never take notice of us watching them, unless the talk is interrupted by a man entering the scene, claps his hands by saying: ‚Gilles Deleuze, take two’.

If a philosopher renders thinkable what couldn’t be thought before, an artist renders visible the invisible forces of the world, to paraphrase Deleuze and his take on Paul Klee. The role of the artist is yet not to lubricate philosophy, to make it accessible, to illustrate thoughts, but rather to resist the world and its sometimes too common sensual logic. Art is not designed to communicate the obvious, but rather to create new percepts. Deleuze cannot be thought or followed without the references he bases his concepts on. Speaking about Proust and Kafka, about Mahler and Bresson, to name a few mentioned in the Abécédaire, his concepts of de/territorialization and the ritornello, ‚becoming minoritarian’, of becoming foreign in one’s own language, of stuttering and stammering, of proliferation would simply remain bloodless thoughts. Deleuze takes the artists’ work seriously as being inventive, as being creations of a new world, and thus he can read them to help himself create new concepts. Vice versa the cited works of the arts provide us with multiple accesses to Deleuze world, to the aforementioned triad of concept, percept, and affect.

‚Take two’ of this durational dialogue between philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the interviewer and friend Claire Parnet. The beholder (us) is situated at two places at the same time. First, we are placed at the position of the camera eye, following its minimal moves, vertically zooming in on and out from Deleuze’ face. The camera makes us become bodiless Peeping Toms. But secondly, we are rendered present in the position of Parnet, better: her reflection in the mirror behind Deleuze.

We approach Deleuzian philosophy via the back door of creation. Rather than illustrating what Deleuze may ‚mean’ by his concepts, we let ourselves be inspired by the artistic corpus and interpret procedures of creation to make them become productive for our creative processes; at a given moment Deleuze said that one cannot have any idea, one can only have an idea in thus and thus situation. An idea thus is never of an abstract kind since it is related to the environment in which it is developed, in which it becomes effective.

Practices of de/territorialization, ritornello (repetition), making foreign (without alienation), proliferating from the middle (by suspending the logic of beginning and end) impregnate our actual approaches right now. We might produce cultural percepts and re-edit them to make them enter another affective state. Principles of disjointing (breaking down the continuum of sound and image, of language and speaking) and subtracting (taking away prevalent units of narrative in order to look right at the images, at what pierces through), getting behind the narrative: rendering visible what has been concealed to the eye, rendering rethinkable another thought that was built in in another logic, rendering affective what has been called this and that emotion some time before. Disjointing and subtracting make the material resist to their own smoothness, their own logic, give way to, somehow against the grain, what cannot be interpreted or tamed by discourse. Taking apart (disjointing) and taking away (subtracting) aren’t yet operations of reduction in order to clear what’s in the way and break through to the very essence of a given material. Rather, these operations pose a severe problem to the material by cutting through the ambilical chord that nourishes them in terms of narrative or dramaturgy or visual code. Posing a problem is not just interrogating that material by somehow scrutinizing it along the given logic, to make it give answers to certain artistic questions; the operations applied are not just reshaping the original material (the map cannot just be reassembled in another way, the Bressonian hands of ‚pick-pockets’ cannot just be removed from the situation they are in; the Godard clips are not only cut into and framed by a new temporal logic), this is not about altering classics in order to rejuvenate them or have them rearranged due to one’s own questions; these rather anatomical incisions into the flesh cut out what once was their reason of existence, their heart beat, their vital force.

We put them into the emergency room, provide them with as much intensive care as to create another monster: the fissures that hold it together, the tubes that nourish it, the incubator that makes it grow are still visible. We cut deep, cutting through vital organs, maybe take them out (who cares since we are not interested in the business of organ transplantation, of passing on vital forces from a moribund to a more promising exemplum of the arts), but the monster knows how to walk, how to talk, how to breath in and out, but the monster renders visible the brutal forces that are at work at functional bodies, but the monster poses a problem to itself not because it wants to be more perfect, not since it creates a desire for beauty or intelligence, but because it’s difficult not to forget about how to put one step in front of the other. It knows how to walk but it can barely walk. Every translocation renders visible the labour (yes, both work and pain of giving birth), every attempt to communicate ends in infinite murmuring and stammering, in stuttering and sonic proliferation. We may want to pose problems that problematize that which has been producing reliable percepts and affects. If someone takes away the letter ‚e’ in a novel after a while the reader adapts to this disappearance and fills in an imaginary ‚e’. But if you keep doing a similar operation, when would you have to face the impossibility that you are no longer able to add what is missing? When would the act of reading become dysfunctional and an act of writing instead would have to take over? This is what the operation of subtracting does: it forces to commit to the creative act, yet an act of creativity that is not slick but that needs constant work, like someone who has something (an obstacle) in his mouth which is simply too big to chew on or even to spit out, and yet that individual is asked to make a speech. What we would hear after a while, what we would try to filter out are the noises accompanying that speech, the smacking saliva, the unelegant, even rude articulation, the slurring of words, but we could also hear the resistance, not just of the individual who keeps doing what he is asked to (giving a speech), but also the resistance of language itself. Confronted with a problem means to look at the forces of resistance, of what holds itself against the problem, and at the forefront the forces of resistances are equal to the forces of creativity. This, by the way, is the difference to an aspired critique of a given work, a canonized theory: a critique wants change since the criticizing subject feels that the critiqued is in crisis. A crisis being the state of transformation in which the old is already bypassed and the new not yet at sight. Critiques operate from a threshold in-between old and new spaces. If one confuses resistance with critique, then resistance would already be at service of the discontent. Our operations don’t strive to criticize the original format of the medium or thought or practice used, even though at a certain moment they may lead to a temporary break-down or stand-still of the original medium; we rather make the units undergo such operative forces in order to experience the resistance both of the structure (bones) and the vitality (flesh).

Parnet’s position is rendered visible, at the same time 1) being at the place of the structurally invisible, of the interviewer who asks questions out of the dark, and 2) witnessing herself in the reflection. She, a double-headed monster, at the same time captured with the back of her head and the front of her face. Her double image opens up the field, a territory in which Deleuze dwells in order to think, to reflect, to talk, he who sings his tune like the birds he speaks about in ‚A Thousand Plateaus’, who is at home in his living room, his arm chair, in his gestures, and in his peculiar voice.

This is what offers itself to be done as well, to a certain extent, with the philosophy of Deleuze as it is displayed in the ‚L’Abécédaire’. Not to prove him wrong, or to improve his thoughts, not to criticize by claiming a state of crisis in the way how he is putting forth his discourses, this is neither about going with nor against Deleuze. We have already discovered that ‚L’Abécédaire’ is a collection of pre-thought discourses, concepts that already have been published in the various writings of Deleuze. We have already found out that the premise of the clause that forbids an airing of the dialogue before his own death is somehow coquettish. There is yet nothing to criticize. The alphabet’s rule is covered by its contingency. What then might be the forces of disjointing and subtracting that could become operative? It’s not about rearranging phrases, changing their orders to create another, even reverse meaning (a procedure propaganda departments or comedy companies would undertake, with different purposes of course) in order to criticize or, to use the philosophical operation, to deconstruct the ideology hidden in the utterance – this would function within the conceptual paradigm of philosophy; getting in-between Deleuze’ logic of sense (a paratactical, infinite discourse that tells the content of each sentence in the subsequent one) where one might substitute the precedent sentence with the one following to turn the argument upside-down (like rearranging the order of images in a movie and then call it a ‚flash back’) is also not what incisions are about which cut into the temporal succession; one should try to get in-between the images, exactly where parole hasn’t fully been formulated, in-between the breaths, Deleuze pneuma, his tuberculous rattling where discourse is interrupted by a physical strain, an act of resisting. And yet: what resists what, is language resisting the physiology or does physiology resist language?

Could one try to get in-between the images, yet not on the temporal axis, the axis of syntagma, but on a vertical vector, into the heart of the image, in-between the framing provided by a) the camera, b) Claire’s shoulder and c) her mirrored face in the looking glass. This would be dealing with the limits of the space of resistance, its demarcation. As if one could try to turn the Cartesian space into a vectorial space, vertical, zooming in. To turn Cartesian space into a rhizomatic space, a space that doesn’t deal with width, but only with depth. A space that could be defined in the words of German philosopher Joseph Vogl: ‚A maze without beginning and end, without Ariadne thread, without centre or periphery, a system consisting of shortcuts and detours. A space of unforeseeable encounters.’ Thus conceived, a rhizom has the quality of a spatial apparatus, and is not merely a figure of thought, of word, a metaphor.

He doesn’t whistle or sing a song in order to become unfrightened, but, uncannily enough, what keeps coming back is his tuberculous cough and his rattling voice. Is he safe and sound in-between the camera, between Claire’s body and her facial image reflected in the mirror behind his back?

Creating a rhizom, and we know about the possible staleness, unoriginality of such an enterprise, then could be operated by the principles of taking apart (disjointing) and taking away (subtracting) which somehow merge (an unforeseeable encounter) to become a third operation, one we haven’t been mentioning very often until now: the operation of de/re-territorialisation. Disjointing and subtracting produce de-territorialisations (taking out elements of their inherent environment) and reterritorialize both what remains and what is taken out. De/re/territorialization and the use of pallets.

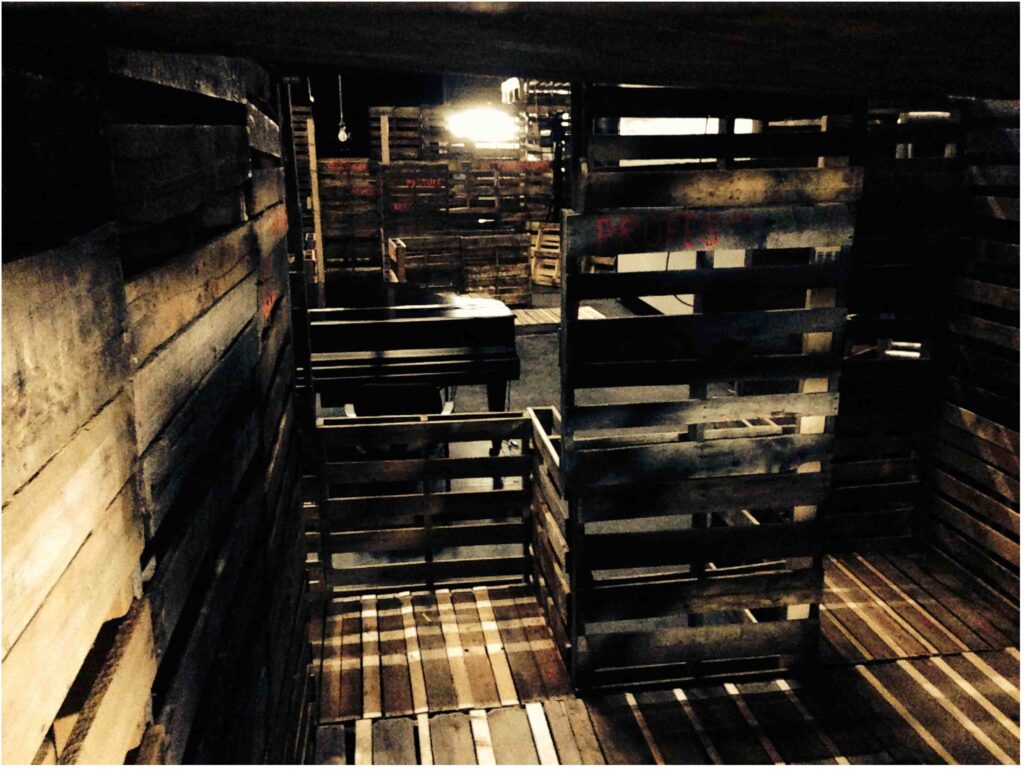

The pallet is a standardized support structure to make the trade of goods possible, to enhance it, to make it smooth. As a means for transportation, it is a medium in the mundane sense of the word for de-territorialization, designed to carry weight without itself having weight and value. We assemble 500 pallets to create modular structures in flux, both using the medium pallet literally as bearer of meaning (stock of pallets piled up to carry themselves) and construction material in order to build spatial mazes. We try to take into account that a rhizom doesn’t provide beginning or end, centre or periphery, simply being a system consisting of detours and shortcuts. There is no linear logic (ante rooms, salon, functionalities) applied but rather we would try to deal with the notion of territorialization as an operative principle. Which might entail that instead of thinking of breadth or length, instead of thinking of syntagmatic logic (like in a parcours where people follow through step by step in order to have a climactic built-up) we might be looking into what I was calling ‚vertical zoom-in’ before. Undoing the different layers, like in an excavation site, cutting into the vertical optical vector, yet not to dig out what temporally comes before but rather to have a vertical (and not horizontal as one might be thinking of in an operation of horizontal displacement) de-territorilization of the compounds that hold together the units of that given logic. What a rhizomatic maze does is not creating temporal or horizontal lines (which then might be gaining value as periphery/centre, beginning/end) but to create folds (as Deleuze was looking into Leibniz’ theories of the monads and the fold) which are endlessly folded down into themselves. Thinking the rhizom as spatial principle allows to start anywhere and thus to integrate spatial (and not only linear as in the alphabet) contingency. The trick of the rhizom, a rootstock, is not to blend in (like an animal that adapts perfectly to the environment) but rather to enhance permeability between inside and outside, to allow for vertical connection, cutting through spatial layers, but not to reach to the origin. Since there is no origin, no source. In ‚What is philosophy?’ Deleuze writes: „All that is needed to produce art is here: a house, some postures, colors, and songs…“. We have all the ingredients at our hand: house (= pallets), some postures (= our bodies), colors (= film), and songs (= music/piano). Houses and songs produce territories. The rest will follow.

A man being at home, chez soi who can say: all that I am going to say right now won’t be aired before my death. I, already a ghost, am talking to Claire and you, absent at the same time. Each take taking me closer to eternity. Taken, too, by 26 letters, addressed to you after my death.

So let’s start, A, B, C, D, as you like it.

Another preface with the help of Lewis Carroll

„If–and the thing is wildly possible–the charge of writing nonsense were ever brought against the author of this brief but instructive poem, it would be based, I feel convinced, on the line (in p.4)

“Then the bowsprit got mixed with the rudder sometimes.”

In view of this painful possibility, I will not (as might) appeal indignantly to my other writings as a proof that I am incapable of such a deed: I will not (as I might) point to the strong moral purpose of this poem itself, to the arithmetical principles so cautiously inculcated in it, or to its noble teachings in Natural History–I will take the more prosaic course of simply explaining how it happened. The Bellman, who was almost morbidly sensitive about appearances, used to have the bowsprit unshipped once or twice a week to be revarnished, and it more than once happened, when the time came for replacing it, that no one on board could remember which end of the ship it belonged to. They knew it was not of the slightest use to appeal to the Bellman about it–he would only refer to his Naval Code, and read out in pathetic tones Admiralty Instructions which none of them had ever been able to understand–so it generally ended in its being fastened on, anyhow, across the rudder. The helmsman used to stand by with tears in his eyes; he knew it was all wrong, but alas! Rule 42 of the Code, “No one shall speak to the Man at the Helm,” had been completed by the Bellman himself with the words “and the Man at the Helm shall speak to no one.” So remonstrance was impossible, and no steering could be done till the next varnishing day. During these bewildering intervals the ship usually sailed backwards. As this poem is to some extent connected with the lay of the Jabberwock, let me take this opportunity of answering a question that has often been asked me, how to pronounce “slithy toves.” The “i” in “slithy” is long, as in “writhe”; and “toves” is pronounced so as to rhyme with “groves.” Again, the first “o” in “borogoves” is pronounced like the “o” in “borrow.” I have heard people try to give it the sound of the “o” in “worry”. Such is Human Perversity. This also seems a fitting occasion to notice the other hard works in that poem. Humpty-Dumpty’s theory, of two meanings packed into one word like a portmanteau, seems to me the right explanation for all. For instance, take the two words “fuming” and “furious.” Make up your mind that you will say both words, but leave it unsettled which you will first. Now open your mouth and speak. If your thoughts incline ever so little towards “fuming,” you will say “fuming-furious;” if they turn, by even a hair’s breadth, towards “furious,” you will say “furious-fuming;” but if you have the rarest of gifts, a perfectly balanced mind, you will say “frumious.” Supposing that, when Pistol uttered the well-known words–“Under which king, Bezonian? Speak or die!” Justice Shallow had felt certain that it was either William or Richard, but had not been able to settle which, so that he could not possibly say either name before the other, can it be doubted that, rather than die, he would have gasped out “Rilchiam!”“

The text (preface) taken from Lewis Carroll’s poem The Hunting Of The Snark, „an agony in eight fits“, resonates with the mode of Deleuzian writing: creating new concepts (‚des mots barbares’: ‚territorialisation’), breaking the logic of the order of things (rhizome vs. tree), creating short cuts instead of lengthy axioms, favouring to a certain extent the non-sensical to make visible the normativity of thoughts, being anecdotical (refering to minor, not so important events to exemplify and at the same time to look at the margins), a writing of thousand plateaus.

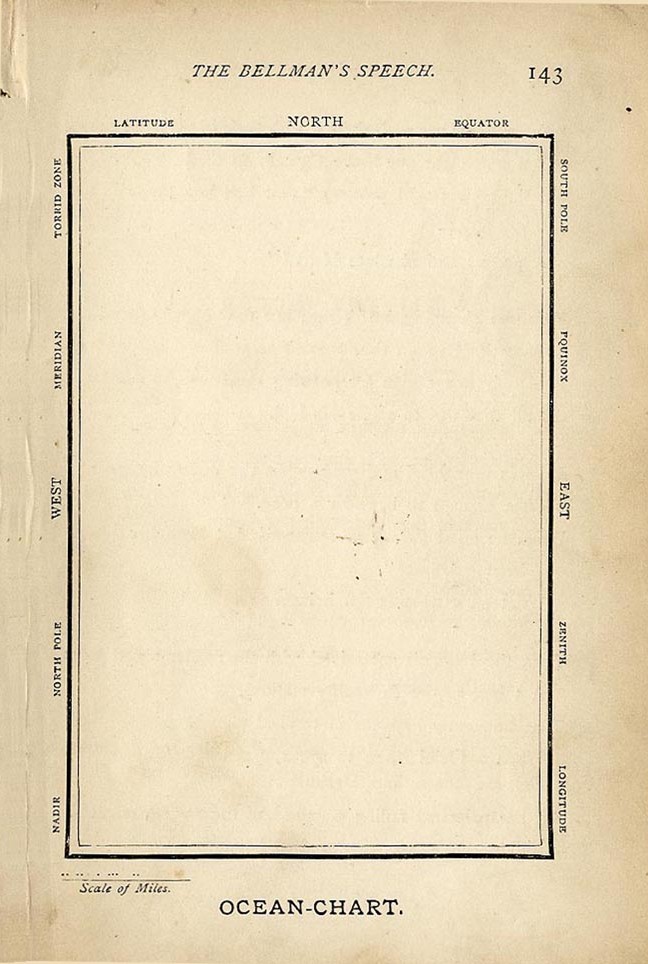

In the first fit (fit meaning if most of all a ‚tic’, a paroxysm, cramp of laughter) of the hunting of the snark, Carroll sets the relation between map and territory straight – in favour of the territory. Snark in itself is a blend, a confusion of words, shortcircuiting snail and shark, a non-sense animal (sic!) that is unhuntable, not unexisting. A chimera:

THE BELLMAN’S SPEECH

The Bellman himself they all praised to the skies–

Such a carriage, such ease and such grace!

Such solemnity, too! One could see he was wise,

The moment one looked in his face!

He had bought a large map representing the sea,

Without the least vestige of land:

And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be

A map they could all understand.

„What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

“They are merely conventional signs!“

“Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we’ve got our brave Captain to thank:”

(So the crew would protest) “that he’s bought us the best–

A perfect and absolute blank!”

A totally white map. What’s the use for that? Rather a frame for imagination than a geographical orientation. And why? Because the world as Gerardus Mercator envisioned it in 1569 is merely a projection. It’s a „conventional sign“, an agreement, an arrangement based on interpretation (that mathematically is not correct): Nothing else. So it’s better to have a blank map than a false one to roam the world when searching for a being that anyway doesn’t have the habit to surface. A smooth space (nomadic) and heterogenuous in contrast to the homogenuous striated space of ‚state’: in a smooth space „there is no line separating earth and sky; there is no intermediate distance, no perspective or contour; visibility is limited; and yet there is an extraordinarily fine topology that relies not on points or objects, but rather on haecceities, on sets of relations (winds, undulations of snow or sand, the song of the sand, the creaking of the ice, the tactile qualities of both).“ (D&G: A Thousand Plateaus) Thus is the Hunting of the Snark, a proto-nomadic tale where maps are negligible because of the actual situation, the constellation of which can be grasped with the ‚tactile qualities of both’. This means that the connection between visual and cognitive, the connection between the eyes and imagination which is asked of when reading a map is useless. The smooth nomadic space is a space where the visual sense is not suspended yet rather equalized. The nomadic space share this with the rhizom: being without optical organisation. It’s the sea in A Thousand Plateaus as Deleuze/Guattari conceive of it which forms a typical example for a smooth space. Since smooth and striated spaces are ALWAYS in transition, there is never one without the other (war/nomads and state), navigation on the sea led to a striated space: at first stars (points) in the sky (astronomy) leading to orientation, then maps (like the one of Mercator’s) which project meridians on the globe. Carroll’s map, empty and „perfectly blank“ thus re-smoothes the sea by not lending any points of orientation once the ship and its crew is afloat.

„First of all a rhizome is a labyrinth, it is a structure of passageways, subterranean, if you will, it’s marked by some properties that distinguish it from the occidental history of the labyrinth. First, it has neither beginning nor end. If it has neither beginning nor end, it is also without an Ariadne thread that is, a labyrinth without centre or periphery. A third characteristics defines the rhizome: it is a structure of passages the metric order of which is so confused that it is unclear which element or place of the labyrinth will take me to the next. It is a system of shortcuts and detours but not of straight and direct paths. These three elements – no beginning or end, no Ariadne thread, centre or periphery -, and finally, a system of passages that consists only of shortcuts and detours – these elements characterise a rhizome. That is why it is the place of the unforeseen encounter.“ Joseph Vogl in an TV interview with Alexander Kluge

The rhizome is a minor space. It’s beneath the surface, there is no coming out of the rootstock. It’s a system, somehow endless with diverse pathways, a mine. It’s an acoustic space (do I hear the enemy?), an olfactory space (is there a leakage? Does this smell of coal?), a haptic space (is this as hard as coal?). The rhizom is the habitat of the mole who cannot see. He is blind. Once he surfaces he wants to disappear. Mineur in French bears these two meanings, a collection of bread crumbs, a lead of French language made for Hänsel to follow through. Does he know where he is going to? Step by step he collects them, eats them and thus cuts the connection to the origin, his starting point. Being lost, he can’t go back, rather has to move on into the darkness of incertainty. Alice beholds the hole in the earth and, moving towards, she slides down, swoosh, falls deeper and deeper, it’s getting dark, she has lost her orientation, blind to common sense and logic (Deleuze speaks about the non-sensical language of the inhabitants of Wonderland; their take on language in regards to its referential function is cut, with Alice being the keeper of common sense – which doesn’t help her). The mole (Alice, the soldier in the First World war, the mining working, Hänsel) is the equivalent of the tick. The tick picks three possible ways to behave within a given world and thus follows three ‚excitants’: light, smell, tactility. Nothing more to make this animal complete.

Becoming tick is not about de-humanizing, this is about becoming human again. Let’s close our eyes for a while and learn how to be in the world blindly…) to sharpen other senses which may have become atrophied.

Becoming rhizome means to understand that spaces grow from the middle without the middle being the centre, and without growing from the start or towards the end. When Deleuze speaks about Peguet this is exactly what he means: a rhizomatic writing from the middle, but in the French sense of the word middle = milieu: from ‚le milieu’ which embraces three supplementary meanings as Massumi points out in his notes on A Thousand Plateaus: „In French, milieu means surroundings, medium (as in chemistry), and middle.“ It’s a concept that is able to marry what is outside (surroundings) with the middle and at the same time to carry or absorb other elements. The middle thus doesn’t have a clear starting point, it rather starts to proliferate from some point, but it doesn’t know where the passage is aiming at.

A closed space (maze) made of 500 pallets

A sonic landscape (atmospherical space)

A musical analysis (lecture demonstration)

A video work (found footage narrative)

Assembling four performative modules (space, music, sound, video) in order to form a dramaturgical structure makes questions (and their discussion) of temporal organisation necessary: do we follow a simple dramaturgy of simultaneity (modules next to each other), do we rather choose a dramaturgy of succession (modules placed after each other)? Both decisions would entail to shift the sense making process fully to the side of the audience whose responsibility of tying different aesthetic experiences together make the work to become a performative installation.

We created a temporal structure in which dramaturgical decision-making is graspable (‚linear narrative‘), yet in which parts of improvisation kept an open space for experiential becoming (‚horizontal aggregate‘). Videos depicting Deleuze’s L’Abécédaire (as source material of the process) associated Deleuze’s philosophy with found footage and were presented on nine different video stations built in the pallet structure. By video live-triggering due to audience response the visitors were made to move from one station to the other. A sonic ‚wash‘ and a musical collage based on music references Deleuze used in the Abécédaire supported or countered the parcours. The atmospheric and narrative elements were interjected by an analysis of musical strategies used by the Avantgarde of 20th century (Alban Berg’s opera ‚Lulu‘ formed the initial starting point), performed live on a grand piano.

Passage ways in a maze-like structure.

26 Letters to Deleuze. ‚Sense‘ is not restricted to one single voice and work. Sense is rather produced within an ensemble, an aggregate (to use Deleuze’s term). Construction of sense doesn’t follow a continuous line through whatever logic (by looking for an Ariadne thread), sense is a celebration of making sense of what is offered to us, of how situations assemble, of how the aggregate of events is folded into each other, without ever revealing their sources or origins; rather by rubbing each other, producing endless constant insides and outsides without the least possibility to distinguish the difference. In this understanding, one can take ’26 LTD’ within the associative forces that reveal themselves once one is ready to sense the percepts being encapsulated in perceptions. A percept being that what survives one’s own experience – a moment of being in contact with another present as one’s own. Contemporaneity, in the words of Giorgio Agamben, means to return to a present where we have never been. Taking into account, embracing the shadows, with a certain affect of nostalgia, not a feeling, but rather a pre-discursive sentiment (affect) to want to return – home.

Production support and residency provided by EMPAC / Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Supported by Goethe Institut New York